Name: Ainash Childebayeva Age: 28 Home town: Almaty, Kazakhstan Area of Study: Biological Anthropology and Toxiclogy Year in School: PhD candidate in the departments of Anthropology and Environmental Health Sciences, University of Michigan

I joined the Everest Base Camp Expedition because… I am interested in how the environment affects the epigenome. I am a PhD student at the University of Michigan researching the epigenetics of high-altitude adaptation in Peruvian Andeans. Andeans, along with Tibetans and Ethiopians, have genetic adaptations to this environment allowing them to thrive in hypoxic (low oxygen) conditions, while visitors often suffer from altitude-associated conditions like Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), and High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE).

It is currently unknown why certain altitude visitors develop adverse outcomes at high altitude, while others successfully cope with hypoxia. Sex, age, and level of fitness do not seem to predict the likelihood of someone developing a condition like AMS. Previous genetic studies of AMS have shown inconclusive results, and it is mostly unknown whether genetic variation plays a role in determining one’s likelihood of developing a high-altitude condition. Being an epigeneticist, I got interested in whether the epigenome could play a role in mediating the effects of high-altitude hypoxia, and if epigenetic variation could maybe help us explain the variability in the high-altitude associated phenotypic outcomes, especially since environmental exposures are known to affect the epigenome.

Some of your might have heard about epigenetics, but for those of you who haven’t, epigenetics as a field studies changes to the DNA that do not affect the sequence of the nucleotides (A, C, T, G). Epigenetic modifications play an important role in human development, and have been shown to mediate the variation between cell types that all have the same DNA, but perform different roles.

For this project, I am interested in assessing DNA methylation, which is an addition of a methyl group (CH3) to the nucleotide Cytosine in the Cytosine-Guanine di-nucleotide. DNA methylation is most commonly associated with gene repression through blocking the gene from transcription. Diet, stress, exposures to heavy metals and toxicants like BPA have been shown to influence DNA methylation.

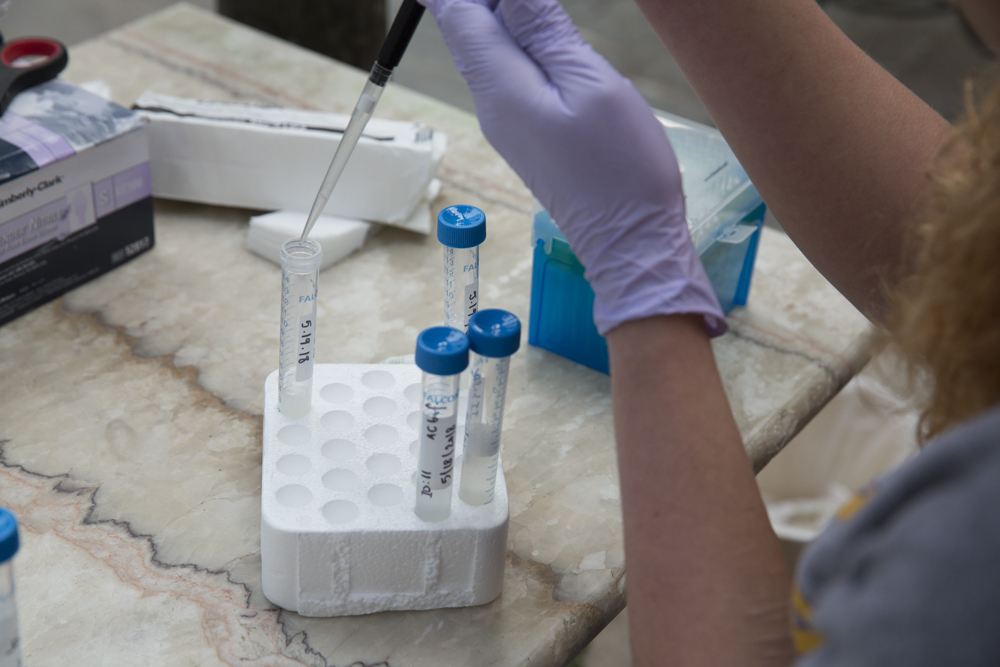

This research hypothesizes that short-term exposure to high-altitude hypoxia would affect DNA methylation. To test this hypothesis, we decided to collect saliva and blood spot samples from the participants of the EBC expedition at different altitudes throughout the trek. So far, we have collected DNA samples from the same participants in Kathmandu (~1400m) and Namche (~3400). We plan to also collect samples in Pheriche (~4300m) and Gorak Shep (~5100m). We will then determine DNA methylation levels in samples collected at the various altitudes and will compare the methylation values in the same participants between different altitudes. We will also test for potential associations between DNA methylation and high-altitude associated phenotypic outcomes.

The samples that we collect here will be transported to the University of Michigan where I will extract the DNA, and will determine DNA methylation at various loci in the genome. Our research is exploratory, since this is the first study to look at epigenetic differences associated with short-term exposure to hypoxia in individuals participating in an incremental altitude ascent. Our results have the potential to inform research in various fields, including high-altitude adaptation, public health, and environmental epigenetics.

I’m involved with the SU research studies by… I am a study participant, as well as a researcher. My role here involves collecting saliva and blood spot samples from the participants of the trek and processing them for transport back to the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor where all laboratory work will take place.

I learned about the Everest base camp (EBC) trek from Dr. Tom Brutsaert when we were in Cerro de Pasco, Peru in the summer of 2017 collecting DNA samples and phenotypic measurements from high-altitude Andeans with my PhD adviser Dr. Abby Bigham. We were eating dinner at Latin Lover, arguably the nicest restaurant in Cerro de Pasco (would recommend! Will eat there again), when Tom told us about the EBC trek he did with Dr. Trevor Day before coming to Peru, and about his plan to take Syracuse students on the same trek in 2018. It was then that we first talked about collecting samples at different altitudes to look for changes in the epigenome in non-native individuals. A couple of months later I received an email from Tom about writing a research proposal to incorporate epigenetics into the main study of the acclimatization to high altitude while trekking to the EBC. Over the course of the year leading up to this expedition we have exchanged copious emails about research design, funding, institutional ethics review board approval, supplies, etc. We are in Nepal now, but It is still hard for me to believe that this project is actually happening, and that we might learn something new about the effects of high altitude on the epigenome.

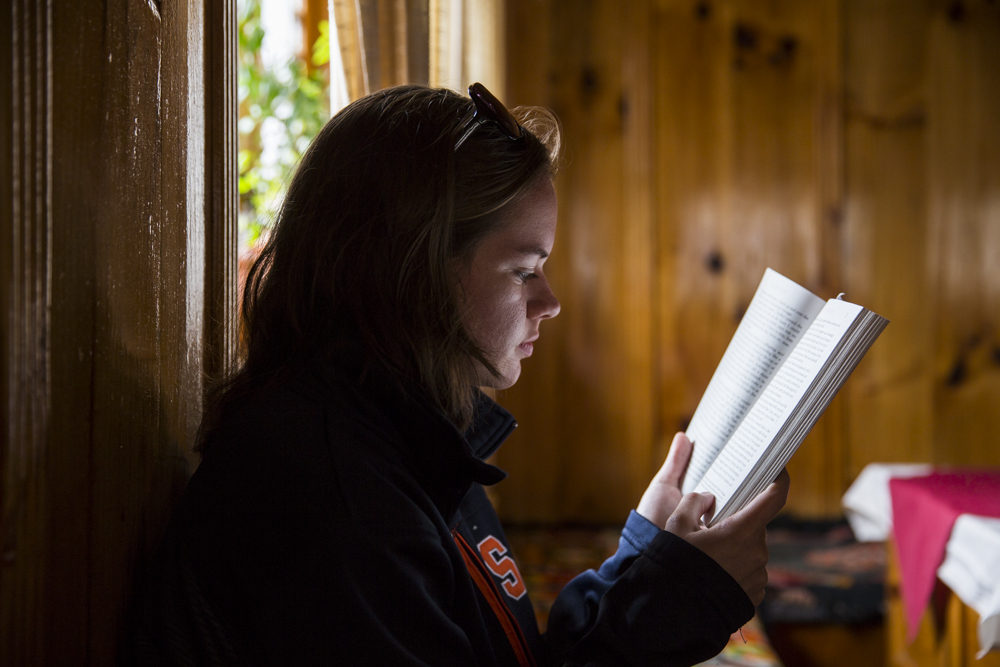

My favorite part of the trip so far has been… Drinking hot, sweet tea in the common room of our lodge in Namche! But seriously, my favorite part of the trip so has been working with the fellow trekkers on the various research components of the trip. The attitudes of the people on the trek and their willingness to help with research and sample collection have been phenomenal. Where else do you find people who are happy to wake up at 6am in the morning, provide a urine sample, a blood sample, and a saliva sample all before eating breakfast?

The worst part of the trip so far… Not knowing how I am going to react to increasing altitude. I have done fieldwork at high altitude before, and have experienced symptoms ranging from vomiting all night to the worst cold I have ever had that didn’t go away until 2 weeks after going back to low altitude. Luckily, we have the world’s best high-altitude physiology researchers on this trip who are constantly monitoring us for the symptoms of AMS. Our ascent includes rest days intended for acclimatization and recovery needed to ensure that all of us make it to Base Camp. I guess I am going to be fine here…

A few things I’ve thought were interesting… A part of the etiquette on the trek is to step aside for porters, yaks, mules, and anyone else carrying loads up and down the mountain. It is a humbling realization that everything we consume on the trek has to be transported up the mountain, most likely by a porter or a yak. It is also important for us to be aware of the waste that we are generating while on this trip. Used lab supplies, bottled water, candy wrappers, etc. will eventually have to be transported down the mountain by the same porters and yaks to be disposed of and hopefully recycled.

One thing most people don’t know about me… I was born and raised in Kazakhstan. I grew up in a city called Almaty, surrounded by the Tian Shan mountains. In Almaty you can see the mountains from almost anywhere in the city. Up and down are the most common ways people indicate locations, and you always know where you are in the city just by finding the mountains, which are on the south side. I like to think that growing up in the presence of beautiful mountains was the reason why I got so interested in high-altitude research.

Daily Recap

We are in Namche today. The altitude here is about 3400 meters above sea level. This is the first day that we are at high altitude, and I definitely felt it when walking up the stairs from the coffee shop where I was able to get a nice cappuccino and much needed Wi-Fi.

Today is our first rest day. I woke up at 5am to prepare for sample collections that started at 6am. We have been able to speed up our sample collection by combining hemoglobin finger pokes and blood spot collection, and it only took us 2 hours to collect both saliva and blood samples from our participants.

In the afternoon, we had a lecture by Tom Brutsaert that explained why we hyperventilate at high altitude. Evidently, as the barometric pressure goes down, the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood goes down, and that results in increased ventilation. Dr. Trevor Day talked to us about his recent publication of a case study of a Sherpa woman who trekked to the Everest Base Camp while 7 months pregnant. This is the first study to document the effects of altitude on a pregnant female performing high-level activity while exposed to extreme hypoxia. The Sherpa woman gave birth to a healthy baby, and we will get a chance to meet the woman and her baby on our way back from the EBC.

Tomorrow we are hiking to Debouche (~3800m), and will have another rest day there that will allow us to adjust to the higher altitude. We will collect daily measurements there, but will skip saliva and blood sampling.

(All photos by Andrew Burton, © 2018)