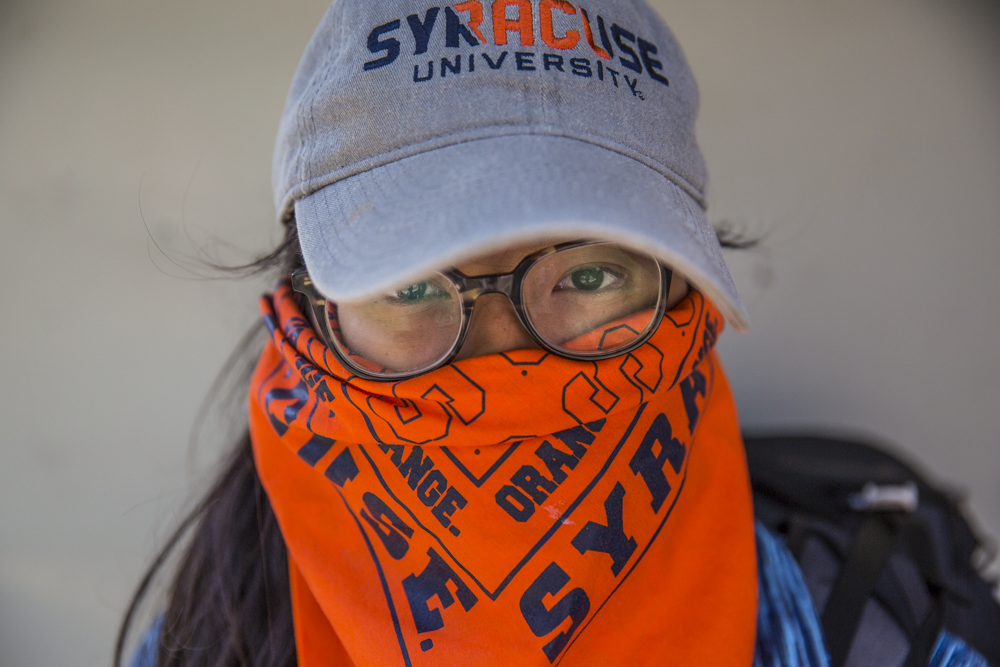

Name: Taylor Harman Age: 21 Home Town: Rocklin, California Area of Study: High Altitude Physiology and Genetics Year in School: PhD Student

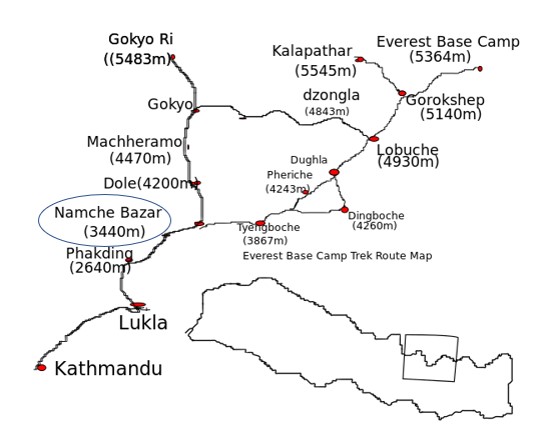

I joined the Everest Base Camp Expedition because… Tom Brutsaert, one of our fearless leaders, is my graduate advisor. He studies high altitude physiology and genetics, which I’m also interested in pursuing. He mentioned this trip to me when I first started attending SU, and framed it as an opportunity to not only see an amazing part of the world, but to get my first experience with high altitude research in the field. I came to graduate school directly from my undergraduate studies, where I studied molecular biology and worked in an epigenetics lab. That being said, I spent a lot of time doing lab work, and very little time doing field work. I thought this trip would be a great opportunity to dive head first into field research.

I’m involved with the SU research studies by… I’m assisting with the SU research in several capacities. My primary job for this expedition was to perform the baseline testing at SU that took place a few weeks prior to departure. While Wes and Jacob ran the cardiovascular side of the research, I ran the respiratory side. For all of our SU students, the respiratory testing involved performing both a Richalet test and an isocapnic HVR test. The Richalet test is a hypoxic exercise test first designed by a French scientist named, you guessed it, Richalet. For this test, the participants were seated on a cycle ergometer (terminology for what is essentially a fancy stationary bike) while hooked up to a mouthpiece. This mouthpiece allowed us to control how much oxygen our participants breathed, and additionally allowed us to measure ventilatory flow, tidal volume, and oxygen & carbon dioxide levels. The participants were also outfitted with a forehead sensor which measured both heart rate and arterial oxygen saturations. As you can probably imagine, this setup is a bit bulky and not the most comfortable to exercise in. However, all of these measurements provide us with valuable data on our participants’ physiology, which we hope can help us predict their performance at altitude. The Richalet protocol is composed of four 4-minute stages. The participants go from resting and breathing room air, to resting and breathing hypoxic air (at about half the normal oxygen level), to biking and breathing hypoxic air (which all the students will tell you was quite uncomfortable!), to finally biking and breathing room air. The results from this test give us important data about our participants’ reaction to hypoxia in both a resting and exercising state. Given that this trek involves both resting and exercising at altitude, we thought it was important to replicate both conditions in the lab.

The second respiratory test we performed in the lab, the isocapnic hypoxic ventilatory response test (aka the iHVR), is similar to the Richalet test. However, instead of exercising, the participants are seated for the entirety of the test, and they simply go from resting and breathing room air to resting and breathing hypoxic air. The hypoxic air for this test was even more oxygen deficient, cut to a third of the normal oxygen level. Though this test does not offer the exercising condition like the previous test, it imposes a greater hypoxic stress, which produces a more pronounced physiological response. This test essentially allows us to quantify how much faster and deeper individuals breathe when exposed to a lack of oxygen. Everyone tends to breathe at least a little bit more when exposed to hypoxia, but some individuals will hyperventilate much more than others. This metric is important to measure, as hyperventilation is an essential part of the acclimatization process to altitude. Hyperventilation at altitude is a large part of what allows individuals to maintain oxygen levels in their blood, even when environmental oxygen is low. For some, breathing only one third of normal oxygen levels sounds quite daunting. And it is true that when participants breathe hypoxic air, there is a slim chance that they can pass out. To avoid this, we continuously monitored our participants’ physiological measurements to ensure they weren’t in any danger. If at any point a participant’s oxygen saturation dropped too low, they were immediately returned to breathing room air.

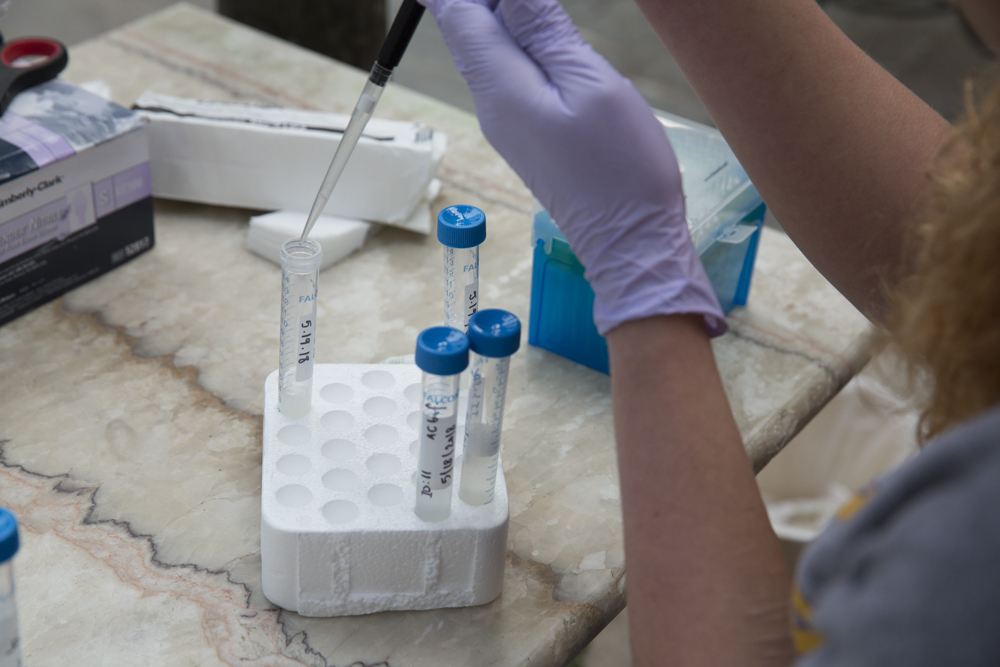

Aside from running all of the baseline respiratory testing in Syracuse, my secondary job for this expedition is to assist Ainash with her epigenetic study. I have training in handling human tissue samples, as well as specific training in handling DNA for epigenetic analysis. Fun fact: Ainash and I actually worked for the same professor (years apart at different universities), and met through our current graduate advisors by total chance.

Last but not least, my job is also to be a participant in every study I’m helping run!

My favorite part of the trip so far has been… As far as the hiking goes, I have to say that the trek from Namche to Debuche has been my favorite. The rhododendron forest was absolutely beautiful. White, light pink, and bright pink bunches of flowers hung from the trees over the trail as we hiked. I’m only sad that my pictures didn’t do it justice. Not to mention, we had a very cute dog that followed us all the way from Namche to Debuche. He was so tired afterward that he plopped right down on the dirt and went to sleep. Aside from the hiking, I think my favorite part of the trip has just been playing cards and other games with everyone. We have a great group of fun, easygoing people on this trip, which has made everything extra enjoyable. We’ve passed quite a few hours laughing and playing games along the way.

The worst part of the trip so far… For me personally, the worst part of the trip so far has been having traveler’s diarrhea. I felt absolutely awful for about four days. I couldn’t hang on to any water or food, and ended up dehydrated. Going through that, as well as assisting with research and hiking for several hours was pretty hard for me. If anything, this trip has made me realize what a baby I am! I’m so used to being coddled while I’m sick, I had a really tough time picking myself up to push through a hike. However, due to the advice of our local soon-to-be doctor Anne and the generosity of everyone else, I seem to be through the worst of the sickness and am now feeling great. Woohoo!

A few things I’ve thought were interesting… One of the most interesting things I’ve seen so far are the interactions between our Sherpa guides and other locals we’ve passed while trekking. Many times I’ve seen them recognize each other, call out each other’s names, and reach out to each other to briefly hold hands. I never expected that there would be so many people they were familiar with, and I think it’s really neat that they seem to have a tight knit community of people, even when most of them are traveling from city to city guiding trekkers, carrying goods, or herding cows and yaks.

Another thing I’ve found interesting is the prevalence of cappuccinos. Here we are above 4,000m and there are still many fancy, tasty coffee drinks to be had.

One thing most people don’t know about me… Something most people don’t know about me is that I briefly worked on a computer science team for an archaeology professor in my undergrad, where I helped program a database for his team to store all of their excavation data. It was this archaeology professor who introduced me to the biological anthropology professor who ultimately inspired my interest in epigenetics. It was also that anthropology professor who connected me with Tom, which lead to me coming on this trip. A series of grand coincidences!

Daily Recap

Today we had our rest day in Pheriche. We’re being put up in a beautiful lodge owned and run by the family of our Sherpa guide Nima. Bright and early this morning we started data collection for several of the research projects. We were sprawled all over the common room, measuring breathing and blood pressures, as well as collecting saliva, blood, and urine. Our hosts have been very gracious to let us use their lodge as our lab space. The mornings of measurements (which we call dailies plus) are always hectic. Researchers double as participants, and the morning turns into a tornado of activity. Somehow, we manage to get it all done in about 2 hours (with a few spills here and there). After the morning measurements, everyone sits down to eat breakfast on the very same tables we were using for research. Everyone seemed quite happy to get a tortilla and egg this morning; yay breakfast burritos!

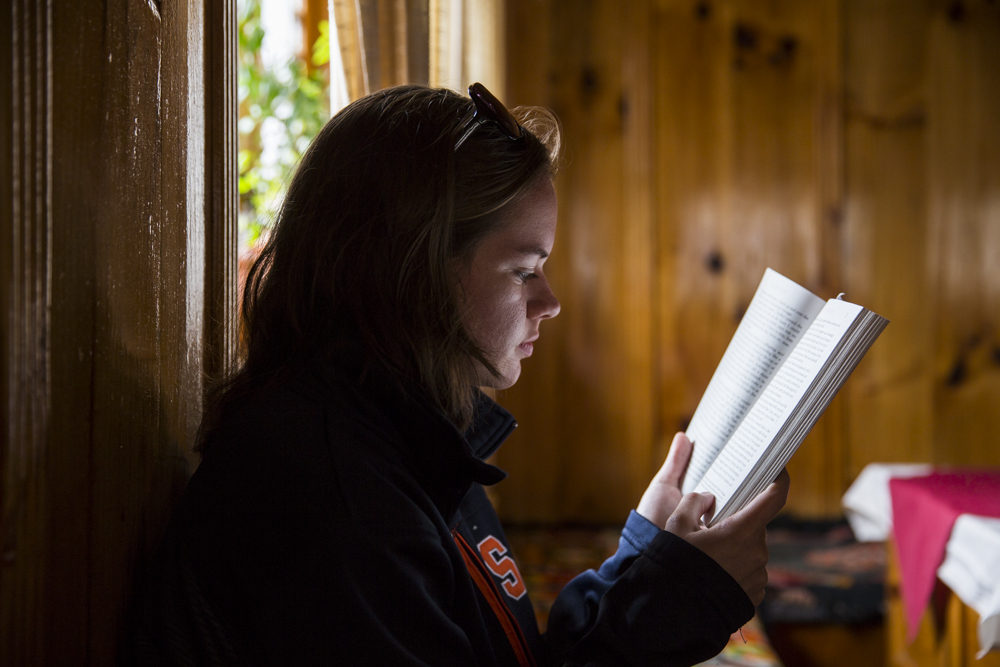

After breakfast, the other, more specific research projects continued. Cognitive function testing for all of the Syracuse students. I can only speak for myself, but the tests are way harder at 4,200m! Additionally, Wes ran a brain blood flow research project on a smaller subset of students with the help of the Canadian team. For all those students and researchers not actively participating or running research, the late morning and early afternoon are free and open. Some students walked down to the memorial for those that died on Everest, others did laundry, and a large group of us sat in the common room and played games.

At one point, we had a group of 14 people playing a game called Werewolf, in which villagers are pitted against werewolves. The game is supposed to be a friendly debate-style game where the villagers attempt to root out the murderous werewolves. However, it usually descends into a verbal bloodbath of accusations and yelling and finger pointing. We may have gotten a bit loud at certain points, yelling that certain players were definitely werewolves and needed to be executed. We may have also been briefly chastised for our volume and language. Whoops.

After games and lunch, we began the academic part of the trip. Tom gave a lecture on his life’s work, researching native high altitude populations. The lecture was wonderful, and even included a small competition between Nima and Trevor. They competed with respect to forced vital capacity (FVC) which is a measure of how much air a person can hold in their lungs. High altitude natives exhibit several physiological differences from lowlanders, including bigger lungs. But the question is: do those bigger lungs actually confer an advantage at altitude? At least in the case of Nima and Trevor, Nima had a notably larger lung capacity, which could confer an advantage at altitude by increasing the amount of oxygen he can take into his body.

Following the academic portion of the day, we moved into dinner, where we had the unexpected pleasure of speaking to an Everest guide who recently summited, as well as a base camp manager. They were lovely, and allowed us to pepper them with all sorts of questions about the work they do. Truly a once in a lifetime experience to be able to pick the brains of two people fresh off of an Everest summit expedition.